How WWII Changed the World

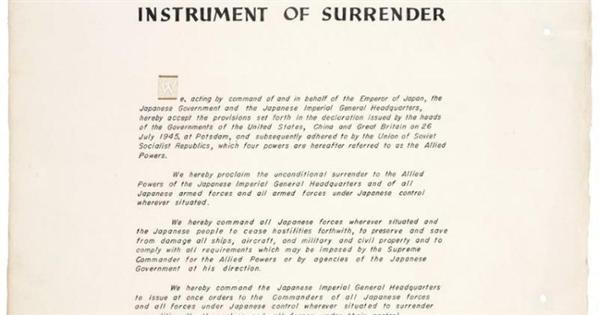

On September 2, 1945, Japan formally surrendered to the Allies, ending World War II and beginning a new era in international relations. The war left a profound legacy, leading to a new international world order, with global power shifting from Europe to the United States and the Soviet Union, and to the rise of multilateralism and a new international framework for peace and cooperation. With European colonial powers weakened, dozens of newly independent nations emerged, altering the dynamics of the international system.

To learn more about these global changes stemming from the end of World War II, we talked with SIS professor and UNESCO Chair in Transnational Challenges and Governance Amitav Acharya, author of the new book The Once and Future World Order. Acharya explains how World War II changed multilateralism, colonization, and the international world order, while also emphasizing the role of nations from the Global South.

- How did World War II change the international world order and the United States’ place in it?

- World War II marked the undisputed emergence of the United States as the global superpower. I say “undisputed” because until then, including the inter-war years, the world was still going through a power transition with Great Britain still holding onto its role as the leading global power. This is usually the period when Britain was willing, but not able, to act as the global hegemon, while the US was increasingly able, but not willing, to take on global leadership. This changed after World War II.

- While Britain and its European allies were on the winning side as part of an alliance with the US, they were too exhausted by the war. Meanwhile, the US came out relatively unscathed and perhaps even stronger than before, with a booming war industry, being the only country to have developed and used the nuclear weapon before the war ended. To be sure, the world had two superpowers, with the Soviet Union matching America’s nuclear and rocket capability, but the USSR had suffered at least 20 million casualties, likely even more, whereas the US suffered just over 400,000 war deaths and was economically in a much stronger position. So, while technically a bipolar world, it was an American hegemony.

- The US was now in a position to build new alliances and institutions to cement its dominance. Some of these were military alliances, like NATO, to defend against the communist threat, while others were multilateral institutions, like the UN system, to provide avenues of cooperation, albeit under the general dominance of the US and its Western allies. This is what later came to be known as the Liberal International Order.

- Dozens of countries gained their independence in the years following World War II—some after weakened European powers willingly granted independence, and others after bloody and protracted wars. How did World War II lead to decolonization and the emergence of newly independent states like India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Israel, and more?

- In an important sense, it was decolonization, rather than the two World Wars, that was the main event of the 20th century, shaping the contemporary world order. The decolonization process had started well before WWII, especially with the Latin American countries, but WWII did give a boost to the process as the European colonial powers were exhausted by the war and found it difficult to hold onto their colonies.

- However, there were other reasons for decolonization. One is the rise of anti-colonial sentiments within the elite opinion of the colonial powers themselves, some of whom felt colonization did not pay as much as claimed and actually burdened their own country’s economy. But this thesis should not get as much credit as Western historians tend to assign it. The really powerful factor was actually anti-colonial movements—some non-violent, as in India; others violent, as in Indonesia, Vietnam, and Algeria—in the colonies themselves.

- Some scholars also argue that US opposition to colonialism also contributed to its end, but this conventional view of the US position on decolonization has been contested, including in my new book The Once and Future World Order. The US support for decolonization was limited—or at best, half-hearted—in deference to its main war-time ally Great Britain, led by Winston Churchill. Churchill strongly opposed the discussion of colonialism during and after World War II, so much so that the San Francisco conference that drafted the United Nations Charter barely mentioned colonialism. Moreover, the limited nature of the US support for decolonization had to do with the fear that it might lead to communist takeovers in the decolonized nations.

- Hence, anti-communism took precedence over decolonization, especially under Presidents Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower, with the latter’s secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, playing a leading role in it. In Indochina, including Vietnam, the US supported continued French colonial rule against the forces led by Ho Chi Minh, fearing the latter’s victory would have a domino effect leading to the communist takeover of all of Southeast Asia. The US also opposed the Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung in 1955, a gathering of 29 newly independent nations whose main goals included advancing decolonization and opposing racism, because it feared that the conference could give legitimacy to communist China, which was in attendance. Here, the US acted in concert with Great Britain, which still wanted to hold on to its substantial number of overseas colonies to disrupt or manipulate the outcome of the Bandung conference (through its allies attending the conference), although it did not succeed.

- Overall, I believe the main reason why decolonization happened had something to do with WWII, but this must not detract from the vital role of the anti-colonial movements in the colonies, which were already growing in vigor and came to enjoy more political support after the initial group of colonized nations, such as India and Indonesia, became independent.

- After two world wars, Allied leaders wanted to build a more peaceful and cooperative global order. Why was it important to them to create multilateral organizations like the UN and World Bank, and how successful have these organizations been in achieving the original goals?

- It is true that the US under President Franklin D. Roosevelt cherished a cooperative world order guided by a genuinely inclusive multilateralism, hence his support for the creation of the UN system. But it should not be forgotten that this had to do with reasons of both self-interest and normative goals. Multilateralism expands the stakes and gives a voice to weaker powers, and as the leading power in the world, it proved useful to the US in reducing resentment against and opposition to its dominance, or “legitimizing” its hegemony in the world at large. Second, the US had no fear of losing control of the most important institutions, either on its own or through its allies, like Britain and France. Indeed, two of the most powerful multilateral institutions to this day, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, have still largely been led by an American or a Western European. Out of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, three are Western. The US did not put all its eggs into the basket of inclusive multilateral institutions of diverse nations; however, it also created NATO—an exclusive military alliance of like-minded nations, which despite its post-Cold War expansion to include former Soviet bloc nations, remains utterly dependent on American power. The US also created a hub-and-spoke of bilateral military alliances in East Asia, with itself being the dominant hub. NATO remains alive to this day, despite Trump’s threats to undercut US commitment to it.

- That said, the UN system has had other contributors and stakeholders. People don’t realize that 30 out of the 50 nations that drafted the UN charter were from what is today known as the Global South. While they did not have leadership roles in various drafting committees, with exceptions like India, they nonetheless had a voice, especially when it came to anti-racism, economic and social development issues. And as the post-WWII period rolled on, more and more decolonized nations took on the task of strengthening and expanding the UN system’s role in global cooperation. What the UN creators missed due to negligence or pressure from US and Britain, such as in the areas of global human rights, anti-colonial and anti-racist norms; the gatherings of newly independent countries, like the Bandung Conference in 1955, filled the gap and advanced them further.

- Overall, the multilateral system created after WWII, despite all its flaws and limitations, has made a major contribution in fostering free trade, economic development, financial stability, and global security. In so doing, it has benefitted from acquiring more support and participation from the postcolonial nations. But the system is failing now, because leading nations like the US feel they can no longer control its agenda or monopolize its leadership and have thus turned against it or grown lukewarm in their support for it. The system is in need of serious reform, but this remains quite elusive because of lack of trust among the major powers. In the meantime, regional institutions such as the EU, ASEAN, African Union, Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank have emerged, partly to fill the gap created by the limitations of the UN system. This pluralization of multilateralism and global governance need not be a bad thing, as long as they complement each other rather than work at cross-purposes.

- Eighty years on, what aspects of the international world order, decolonization, and multilateralism are still a legacy from World War II and what has changed?

- International or world orders, like nations and states, come and go. Change is inevitable. But change should be and can be managed peacefully and in a much calmer and effective way than what we see now. At the end of WWII 80 years ago, the world was still very much dominated by Western powers, with the US as the “new” leader replacing Great Britain. Colonialism was still very much alive. Now we have already seen a global power shift, with the rise of the ‘Rest.’ I have actually called it the “return of the Rest,” since many nations of the Global South were themselves leading powers 500 years ago. China and India were the world’s leading economies for a very long time. All civilizations—Sumer, Egypt, India, Persia, India, China, Islam, Africa, pre-Colombian Native American civilizations like the Inca, Maya, Iroquois—have created world orders of their own and contributed to the fundamental ideas and institutions of the contemporary world order. Even the world order that emerged after WWII was not a Western monopoly. World War II thus created a turning point, a major one, but it did not and should not obscure the legacy of the prior constructs and contributions, in creating institutions such as independence of states, diplomacy, peace treaties, economic, openness and humanitarian values that the post WWII system entrenched.

- In the final analysis though, I believe the most important legacy of WWII is multilateralism, which is under assault today from the forces of populism, nationalism, and unilateralism. But it is this “ism” or institution that we should preserve at all costs, through the needed reforms and innovations that reflect the contributions of multiple civilizations and nations.